Knossos is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and considered as Europe’s oldest city.

The name Knossos survives from ancient Greek references to the major city of Crete. The identification of Knossos with the Bronze Age site is supported by tradition and by the Roman coins that were scattered over the fields surrounding the pre-excavation site, then a large mound named Kephala Hill, elevation 85 m (279 ft) from current sea level. Many of them were inscribed with Knosion or Knos on the obverse and an image of a Minotaur or Labyrinth on the reverse, both symbols deriving from the myth of King Minos, supposed to have reigned from Knossos. The coins came from the Roman settlement of Colonia Julia Nobilis Cnossus, a Roman colony placed just to the north of, and politically including, Kephala. The Romans believed they had colonized Knossos.[6] After excavation, the discovery of the Linear B tablets, and the decipherment of Linear B by Michael Ventris, the identification was confirmed by the reference to an administrative center, ko-no-so, Mycenaean Greek Knosos, undoubtedly the palace complex. The palace was built over a Neolithic town. During the Bronze Age, the town surrounded the hill on which the palace was built.

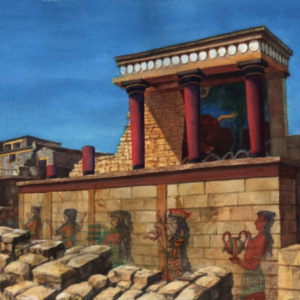

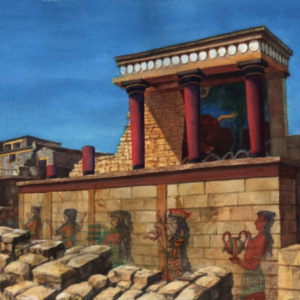

The palace was excavated and partially restored under the direction of Arthur Evans in the earliest years of the 20th century. Its size far exceeded his original expectations, as did the discovery of two ancient scripts, which he termed Linear A and Linear B, to distinguish their writing from the pictographs also present. From the layering of the palace Evans developed de novo an archaeological concept of the civilization that used it, which he called Minoan, following the pre-existing custom of labelling all objects from the location Minoan.

The palace of Knossos was undoubtedly the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. It appears as a maze of workrooms, living spaces, and storerooms close to a central square. An approximate graphic view of some aspects of Cretan life in the Bronze Age is provided by restorations of the palace’s indoor and outdoor murals, as it is also by the decorative motifs of the pottery and the insignia on the seals and sealings.

The palace was abandoned at some unknown time at the end of the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1380–1100 BC. The occasion is not known for certain, but one of the many disasters that befell the palace is generally put forward. The abandoning population were probably Mycenaean Greeks, who had earlier occupied the city-state, and were using Linear B as its administrative script, as opposed to Linear A, the previous administrative script. The hill was never again a settlement or civic site, although squatters may have used it for a time.

Except for periods of abandonment, other cities were founded in the immediate vicinity, such as the Roman colony, and a Hellenistic Greek precedent. The population shifted to the new town of Chandax (modern Heraklion) during the 9th century AD. By the 13th century, it was called Makruteikhos ‘Long Wall’; the bishops of Gortyn continued to call themselves Bishops of Knossos until the 19th century. Today, the name is used only for the archaeological site now situated in the expanding suburbs of Heraklion.

hania after the Venetian urban core. It is constructed on a plot of land covering 12 acres, with a total area of space measuring approximately 6,000 m2 and with a magnificent view over much of the city, especially the seafront. The Museum, designed by architect Theofanis Bobotis and partners, is composed of two distinct linear masses rising from the earth, a symbolic reference to the vestiges of civilization beneath the ground. Constructed to international standards according to the basic principles of public buildings, it is a dynamic and immediately recognisable building, a landmark for the whole city.

hania after the Venetian urban core. It is constructed on a plot of land covering 12 acres, with a total area of space measuring approximately 6,000 m2 and with a magnificent view over much of the city, especially the seafront. The Museum, designed by architect Theofanis Bobotis and partners, is composed of two distinct linear masses rising from the earth, a symbolic reference to the vestiges of civilization beneath the ground. Constructed to international standards according to the basic principles of public buildings, it is a dynamic and immediately recognisable building, a landmark for the whole city. The Maritime Museum of Crete is housed at the Venetian Firka fortress, placed at the entrance of Chania’s harbor. This location has a historical importance, because on December, 1st, 1913, the Greek flag was raised there and signaled the unification of Crete with the Greek state. The initial idea behind the museum was to build a place that would depict the Greek naval tradition and especially the naval history of Crete.

The Maritime Museum of Crete is housed at the Venetian Firka fortress, placed at the entrance of Chania’s harbor. This location has a historical importance, because on December, 1st, 1913, the Greek flag was raised there and signaled the unification of Crete with the Greek state. The initial idea behind the museum was to build a place that would depict the Greek naval tradition and especially the naval history of Crete. The Samariá Gorge is a

The Samariá Gorge is a  One of the most popular spots offering a panoramic view of

One of the most popular spots offering a panoramic view of

The “Old Town” consists of the old Venetian harbor and the small Venetian blocks located behind the harbor; it is characterized by narrow and picturesque alleys – similar to an enchanting labyrinth – full of life, and the plentiful remaining Venetian and Turkish buildings.

The “Old Town” consists of the old Venetian harbor and the small Venetian blocks located behind the harbor; it is characterized by narrow and picturesque alleys – similar to an enchanting labyrinth – full of life, and the plentiful remaining Venetian and Turkish buildings.

The town was also

The town was also